The biblical roots of American Thanksgiving

In fashioning a new national tradition, America's founders looked to biblical precedent.

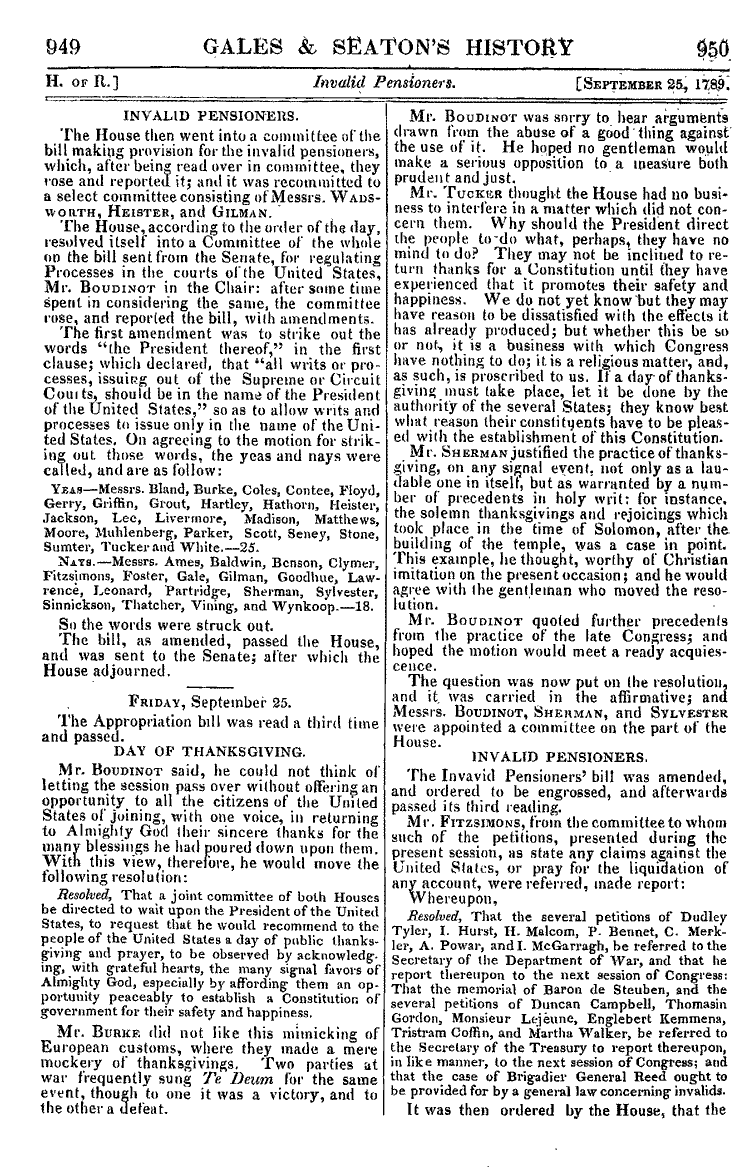

On September 25, 1789, New Jersey’s Elias Boudinot, a member of the newly constituted House of Representatives, introduced a resolution for a national “Day of Thanksgiving.” He “could not think of letting the session pass,” he said, “without offering an opportunity to all citizens of the United States of joining, with one voice, in returning to Almighty God their sincere thanks for the many blessings he had poured down upon them.” So Boudinot’s resolution asked President George Washington to recommend to the American people “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a Constitution of government for their safety and happiness.”

But early America was a fractious place. One congressman objected because, in his view, the federal government ought to stay out of religious matters. Another said “he did not like this mimicking of European customs, where they made a mere mockery of thanksgivings.”

Roger Sherman of Connecticut rose to defend the resolution, arguing that the practice of thanksgiving was not just “laudable in itself” but also “warranted by a number of precedents in holy writ: for instance, the solemn thanksgivings and rejoicings which took place in the time of Solomon, after the building of the temple.”

Sherman’s words carried the day. Boudinot’s resolution was approved by the House and Senate, and President Washington issued his Thanksgiving Proclamation on October 3, 1789. Here let me make three observations.

First, as with many things providential, the timing of events is noteworthy. Solomon’s dedication of the temple in Jerusalem, narrated in 1 Kings 8, occurred in the Hebrew month of Ethanim (or Tishrei), which roughly corresponds to our September and October—the same time of year when Boudinot’s resolution was introduced and Washington’s proclamation issued. (Of course, we now celebrate Thanksgiving on a Thursday in late November, but that was a later development based on a precedent set by President Abraham Lincoln so that the holiday would coincide with the all-important Dallas Cowboys football game.)

Second, in fashioning a new national tradition, the American founders looked not to European examples but to biblical ones. The historical precedent that carried the day wasn’t the Holy Roman Emperor but Israel’s king—a ruler who, like the new American Executive, was to be chosen from among his “brothers” and subject to law (Deut. 17:14-20). The Bible’s importance to the founders is often underappreciated. Boudinot, for example, went on to become a founder and the first Chairman of the American Bible Society.

Third, in reading both Solomon’s prayer of dedication and Washington’s proclamation of thanksgiving, one is struck by the parallels: acknowledging the nation’s dependence on God, seeking His continued favor, praying forgiveness for sins both national and individual, and expressing the hope that the nation might be a light to others:

“In order that all the peoples of the earth may know your name and fear you, as do your people Israel,” King Solomon prayed, “and that they may know that this house that I have built is called by your name.”

“To render our national government a blessing to all the people,” President Washington likewise implored, “to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shewn kindness unto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord.”

These are aspirations both particular and universal: particular because they are grounded in experiences unique to a specific nation, but universal because they express the hope that the nation will be a model, a blessing, and a guide to all.

How precious this heritage we have: heirs of the biblical tradition, beneficiaries of the American experiment in ordered liberty. I am grateful for this heritage. May we continue to steward it well.