The Federalist in a Year, With Poetry

Defending the Constitution in verse

The United States is a unique constitutional republic, and it requires a particular kind of citizen to steward and sustain it. The American experiment in ordered liberty, now almost 250 years old, requires citizens who are shaped by and committed to a particular set of foundational ideas:

The responsibilities of self-government

Civic virtue

Political equality

Representative democracy

Limited government

Respect for minority rights, including religious freedom and free speech.

These are essential features of our constitutional republic—the conceptual and institutional structures on which our law and political culture are built. Without them, the United States would not be what it is. And without an understanding of them, the American people can neither sustain their republican experiment nor carry it forward.

The trouble is, while the institutions of our national civic life require a particular kind of citizen, they do not themselves create such persons. Nor should they be expected to. They were not designed that way. As Yuval Levin puts it in his recent book American Covenant:

“Our politics requires a kind of person it does not produce by itself, and so it must depend on other institutions of our society to produce that person.”

These other institutions include the family, community, religious tradition, and other civic and educational institutions. (Whether these institutions are today fulfilling that responsibility is a separate, albeit crucial, question.)

To understand American political institutions, the natural starting point is of course the Constitution itself. It’s a fair bet that most Americans haven’t ever read the document in full. They should. It’s only about 4,400 words—7,500 if you count all 27 amendments. (When I taught constitutional law and First Amendment to college undergrads, I gave them all a free copy of the Constitution, and their first reading assignment was to read the thing cover to cover.)

But the Constitution’s meaning isn’t always self-evident or intuitive. To truly understand it, one must know the problems it aimed to solve, the debates it did (and did not) resolve, and the philosophical commitments that drove it. One must know something about the political culture in which it arose.

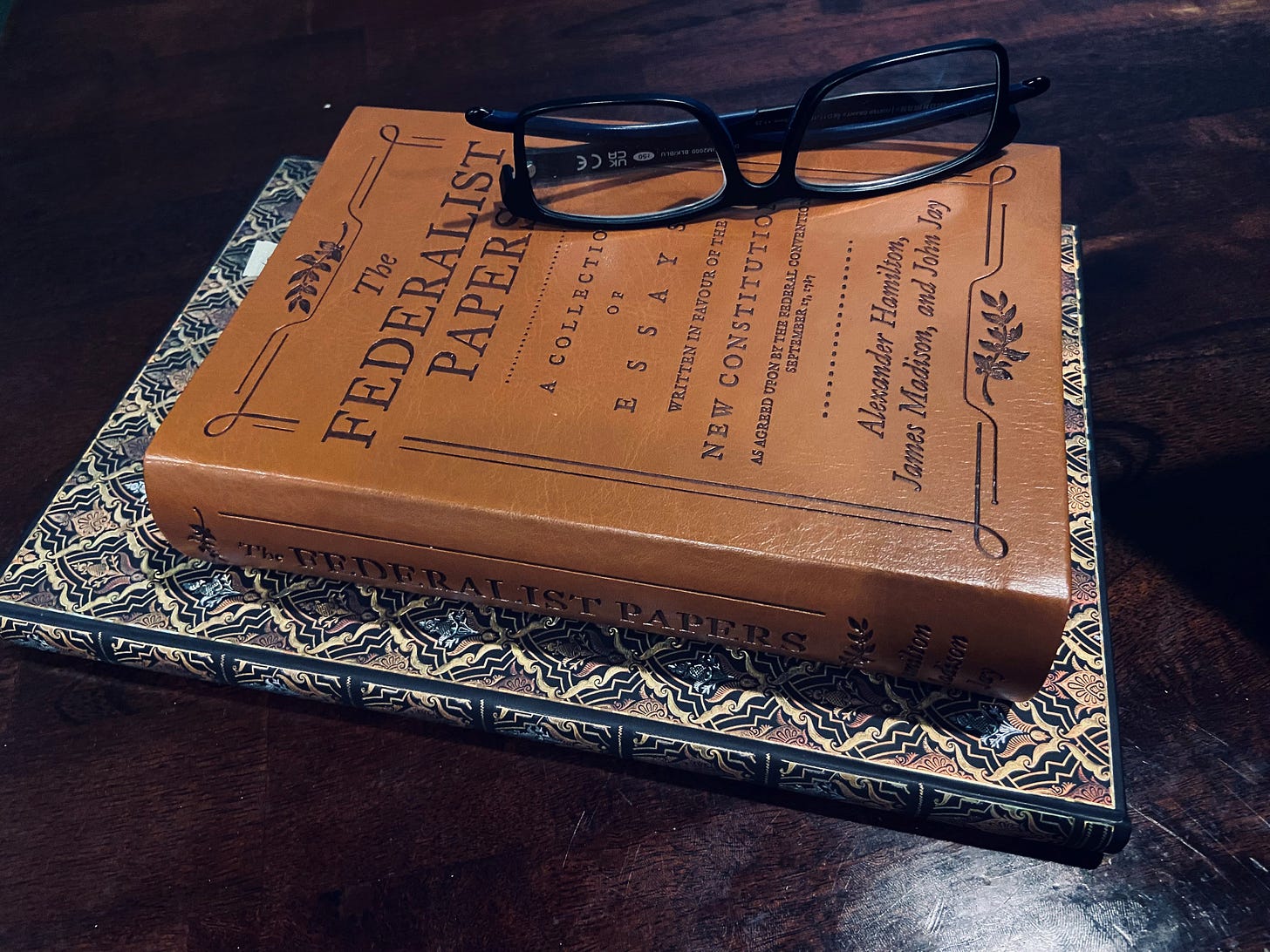

Almost from the beginning, Americans have looked to The Federalist—sometimes called The Federalist Papers—to better understand their National Charter. These were a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pseudonym “Publius” and published in various newspapers, primarily in New York, between October 1787 and May 1788. Their purpose was to advocate for ratification of the new Constitution—sometimes called the “Plan of the Convention”—and to explain, almost line by line, the intent behind its provisions.

The Federalist in a Year

Constitutional lawyer though I am, and despite fancying myself a student of Madison’s thought in particular, I have never actually read all of The Federalist. I’ve read several of the essays in depth; I’ve dipped into various others; but I’ve never read them all.

In 2025, I intend to remedy the defect. Call it “The Federalist in a Year.” At two essays a week, I would be done by October, but I plan to read faster than that.

Of course, the challenge isn’t just to read the essays, but to absorb and be shaped by them. I tend to journal when I read, taking notes, noting quotes. But I plan to do something a little extra. For each essay, I’ll compose a small poem to summarize and help me remember what it’s about. The poems won’t always follow the same format. Some iambic pentameter here, a limerick or haiku there.

Here’s what I cobbled together for Federalist No. 1, which is Hamilton’s general introduction to the essays:

Federalist No. 1

The proposed Constitution is a test of our people

Whether history will repeat or change its course—

May government be founded on reflection and choice,

Or be subject always to accident and force?Views will be mixed. Be guided by truth.

(Everyone’s tainted by their own ambition.)

Let me lay my own cards on the table:

The necessity of Union is my highest conviction.On two things does good government depend:

Energy (the means) and Liberty (the end).

A Tradition of Federalist Poetry

As it turns out, what might be called “Federalist poetry” has a venerable history. Here’s the last stanza of “Our Liberty Tree: A Federal Song” published in the Massachusetts Centinel on December 29, 1787:

Then from east to the west let our Patriots convene,

Determin’d their country to free,

Our Constitution confirm—it firmly shall fix,

Its idol—our Liberty Tree.

Or consider stanza IV of “The Fabrick of Freedom,” published on March 8, 1788, with echoes of Madison’s Federalist No. 10:

Thus is our constitution rear’d,

On Freedom Strength and Peace;

By Virtue lov’d, by Faction fear’d,

For faction’s self must cease.

Contented now we’ll happy live,

While Industry and Trade shall thrive.

Finally, there is what might be my personal favorite: “The New Constitution: A Song.” It’s a kind of constitutional Screwtape Letters. Published in the Virginia Herald on January 10, 1788, the poem envisions Satan and his minions—alarmed that “[a] wonder, a good constitution” has “lately appeared”—stalking about, sowing chaos and deception to defeat the project. The poet urges his countrymen to resist the devilish plot:

Then let each honest man

Do the best that he can,

And establish a firm resolution,

All their schemes to oppose,

And to harrass the foes,

Of this happy and good constitution:

I hope to publish insights from my readings of The Federalist—and more poems—as the year progresses.

I learned a lot from this and you have a unique angle on works that have been analyzed inside and out since the beginning. A tall order, but an imaginative and ambitious project.