Sabbath, anti-Sabbath, and American law

The biblical roots of the day are alive and well in American law and jurisprudence.

The ancient Romans ridiculed the Jewish practice of Sabbath. To a pagan culture obsessed with wealth and power, setting aside every seventh day to cease from work and profit-making seemed quixotic, indolent, and unvirtuous. But the practice has sustained Jewish civilization for millennia. “The Sabbath is a day for the sake of life,” Abraham Joshua Heschel writes in his small yet profound book The Sabbath:

Six days a week we wrestle with the world, wringing profit from the earth; on the Sabbath we especially care for the seed of eternity planted in the soul.1

Early Christians, attendant to the biblical commandment, adopted the Jewish custom but moved the day from the end of the week to the beginning to coincide with Sunday, known as the “Lord’s Day.” (This even though the Gospel writers seem intent on depicting Jesus’s resurrection on Sunday morning as an act of (new) creation, not rest.)

Early American practices

Early American communities observed Sunday Sabbaths and enforced them by law. A 1650 law in colonial Massachusetts provided, “Further bee it enacted that whosoever shall prophane the Lords day by doeing any servill worke or any such like abusses, shall forfeite for every such default tenn shillings or be whipte.”2 A 1705 law in Pennsylvania attached a rationale to the prohibition:

To the end that all people within this province may with the greater freedom devote themselves to religious and pious exercises, be it enacted, etc., that according to the example of the primitive Christians, and for the ease of the creation, every first day of the week, commonly called Sunday, all people shall abstain from toil and labor, that whether masters, parents, children, servants or others, they may the better dispose themselves to read and hear the Holy Scriptures of truth at home, and frequent such meetings of religious worship abroad, as may best suit their respective persuasions….3

Herein, a deeply biblical understanding of Sabbath. It is a day “for the ease of the creation,” for “freedom,” for devotion to higher things, when all people—masters and servants, parents and children—are made equal. Heschel likewise calls Sabbath a day “for freedom,” when we detach from technical and practical affairs and attach ourselves “to the spirit.” “In the tempestuous ocean of time and toil,” he writes, “there are islands of stillness where man may enter a harbor and reclaim his dignity.”4

Even the federal Constitution makes provision for Sabbath. Article I, section 7 requires a bill to be presented to and signed by the President before it becomes law. But:

If any Bill shall not be returned by the President within ten Days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the Same shall be a Law, in like Manner as if he had signed it….

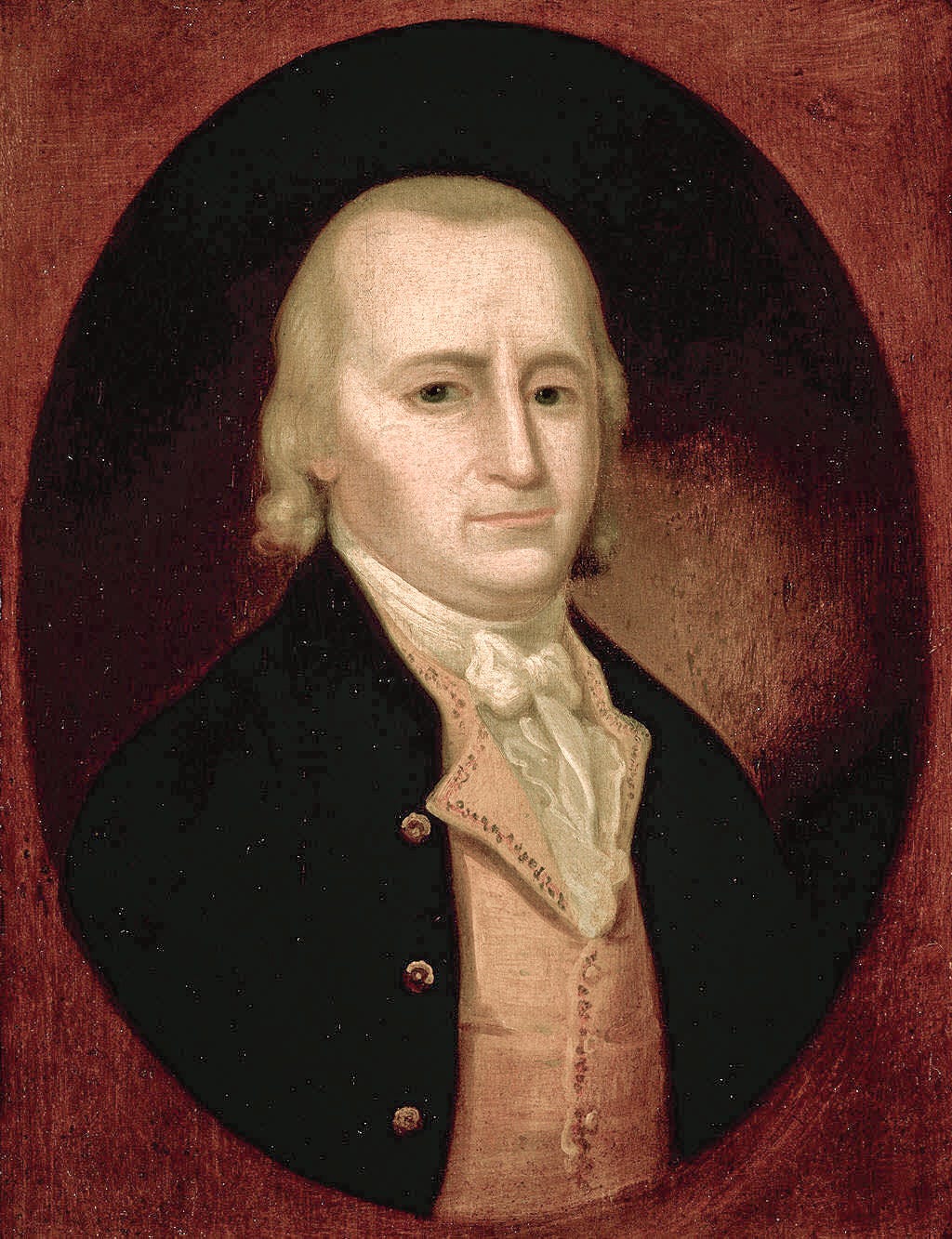

The point was to avoid punishing the President for not working Sundays. And the nation’s first President was indeed Sabbath-observant. An article in the Columbian Centinel in December 1789 relates the following:

The President [George Washington], on his return to New York from his late tour through Connecticut, having missed his way on Saturday, was obliged to ride a few miles on Sunday morning in order to gain the town at which he had proposed to have attended divine service. Before he arrived, however, he was met by a Tything man [a public official responsible for enforcing Sabbath laws], who commanding him to stop, demanded the occasion of his riding; and it was not until the President had informed him of every circumstance and promised to go no further than the town intended that the Tything man would permit him to proceed on his journey.5

It is a quintessentially American tale. The highest official in the land is subject to law—and a Sabbath law at that!

Sabbath laws in American jurisprudence

The first recorded case raising issues of religious freedom after ratification of the First Amendment involved Jewish Sabbath observance.6 The Pennsylvania case report on Stansbury v. Marks is light on details. It relates only the following:

In this cause (which was tried on Saturday, the 5th of April) the defendant offered Jonas Phillips, a Jew, as a witness; but he refused to be sworn, because it was his Sabbath. The Court, therefore, fined him L 10; but the defendant, afterwards, waving the benefit of his testimony, he was discharged from the fine.7

There is more, much more, to this story, which Rabbi Meir Soloveichik traces in his Tikvah Fund lecture series, Jewish Ideas and the American Founding. (The Wall Street Journal offers a short video excerpt here.)

In the twentieth century, as American society modernized and drifted from its biblical roots, Sunday Sabbath laws remained on the books but were subject to legal challenges. One such challenge—again out of Pennsylvania—was Braunfeld v. Brown, in which Orthodox Jewish store owners in Philadelphia argued that the state’s Sunday Sabbath law uniquely disadvantaged them. They closed their stores on Saturdays in honor of the Jewish Sabbath, but state law also required them to close on Sundays, resulting in an entire weekend of lost business. Their non-Jewish fellow store owners, who were open on Saturdays, were not similarly burdened. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the challenge:

[W]e cannot find a State without power to provide a weekly respite from all labor and, at the same time, to set one day of the week apart from the others as a day of rest, repose, recreation and tranquility—a day when the hectic tempo of everyday existence ceases and a more pleasant atmosphere is created, a day which all members of the family and community have the opportunity to spend and enjoy together, a day on which people may visit friends and relatives who are not available during working days, a day when the weekly laborer may best regenerate himself.8

The store owners were denied a religious exemption from the Sunday closing law.

It’s impossible to miss a double irony here. A Christian religious practice with its roots in Jewish tradition punishes observant Jews for their participation in civic life. And a practice with thoroughly religious foundations is transformed into a secular “day of rest.” Thus is the branch cut off from its root.

Yet even in the Court’s reasoning, there is an evident religious vitality. In speaking of the “pleasant atmosphere” of the day and the joy of community when a worker may “regenerate himself,” one hears echoes of Heschel and of the older American laws that planted themselves firmly in biblical soil.

Anti-Sabbath laws

It’s with all this in mind that I read with interest of a New York bill, proposed just this month, that would mandate not that businesses remain closed on Sundays (the historical legal problem), but open. Bill No. A08336 would require that all “food services or food concessions” located at public transportation facilities owned or operated by the New York Port Authority “be provided every day of the week.”

The bill’s avowed target is Chick-Fil-A, one of the country’s most famous Sabbath-observant businesses. New York legislators are irked that the chicken chain’s delicious sandwiches aren’t available to Sunday travelers:

[The] portfolio of companies include Chick-fil-A, which by company policy is closed on Sundays, and which has already opened at seven service areas. While there is nothing objectionable about a fast food restaurant closing on a particular day of the week, service areas dedicated to travelers is an inappropriate location for such a restaurant. Publicly owned service areas should use their space to maximally benefit the public. Allowing for retail space to go unused one seventh of the week or more is a disservice and unnecessary inconvenience to travelers who rely on these service areas.

I know nothing of New York politics and have no sense of the bill’s odds of being enacted. If it does pass, it is liable to obvious constitutional objection. The bill specifically targets a religiously-observant business. And it exempts “farmers markets” and “local vendors,” thus fatally undermining any notion of a compelling state interest in enforcing Sunday commercialism.

One thing I do know: New York is not called the “Empire State” for nothing. The ancient Romans, at least, would be proud.

Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man, p.13 (Farrar, N.Y. 2005) (orig. pub. 1951).

American State Papers Bearing on Sunday Legislation, p.36 (Wm. Addison Blakely ed., Religious Liberty Ass’n 1911)

Id. at 48-49.

Heschel, Sabbath, pp.28-29.

Alice Morse Earle, The Sabbath in Puritan New England, p.75 (5th ed., N.Y. 1892).

Michael W. McConnell, “Free Exercise Revisionism and the Smith Decision,” 57 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1109, 1133 (1990).

2 U.S. 213 (Pa. 1793).

366 U.S. 599, 607 (1961).